Mammogram Screening: Debunking 12 Common Myths That Every Woman Should Be Aware Of

Did you know that one in eight American women will develop breast cancer in their lifetime? In 2024 alone, an estimated 42,250 women in the United States are expected to die from the disease. Even more alarming is the fact that breast cancer is 40% more likely to be fatal for black women compared to white women, despite the availability of some of the world’s best mammogram screening facilities in the country today.

Annual mammogram screening is the most effective way to catch breast cancer early, and it’s the best defense against receiving a late-stage breast cancer diagnosis.

And yet, while the iconic pink ribbon campaign for breast cancer is doing a marvelous job of encouraging community involvement, spreading awareness and raising funds for breast cancer research, mammogram screening – the key tool that makes early detection and treatment possible – remains significantly underutilized.

This disconnect exposes a troubling gap in preventive healthcare. Despite the availability of advanced mammography technology, widespread access and adoption is still lagging behind. Misconceptions about mammograms—whether it’s fears of pain, radiation, or uncertainty about who should get screened—contribute to the disparity, creating barriers to a procedure that can catch breast cancer in its earliest, most treatable stages, lower treatment costs, and ultimately save lives.

National Mammography Day on October 18, 2024, serves as an important reminder to dispel myths and address misconceptions that prevent many women from taking the crucial first step toward early detection and a healthier, breast cancer-free future.

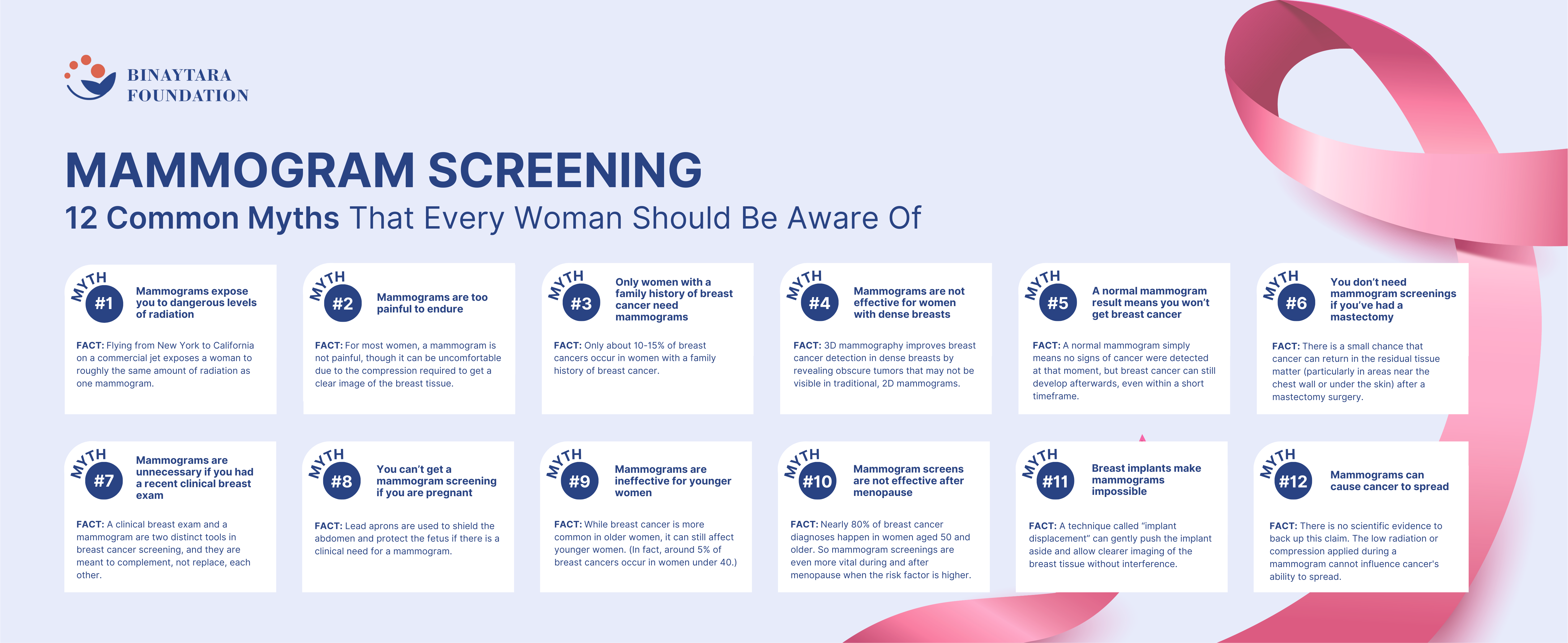

In this article, we will debunk 12 of the most common mammogram myths to encourage women to make informed decisions and take proactive control of their breast health.

Myth #1: Mammograms expose you to dangerous levels of radiation

Fact: According to the American Cancer Society, flying from New York to California on a commercial jet exposes a woman to roughly the same amount of radiation as one mammogram.

We are constantly absorbing radiation from a number of ambient sources, including our homes and our natural environment. The average person in the United States receives an estimated effective dose of about 3 millisieverts (mSv) per year from naturally occurring radioactive materials, such as radon and radiation from outer space, whereas a mammogram screening exposes women to only 0.4 millisieverts (mSv) of radiation, which is approximately the amount they can expect to encounter under ordinary living conditions over seven weeks.

The benefits of getting a mammogram, therefore, far outweigh any potential radiation risks.

Myth #2: : Mammograms are too painful to endure

Fact: Mammogram screenings can cause discomfort, but the level of pain experienced varies widely from person to person. For most women, a mammogram is not painful, though it can be uncomfortable due to the compression required to get a clear image of the breast tissue. The amount of discomfort depends on factors like breast size, the individual’s pain threshold, and the skill of the technician.

With advancements in mammography technology, however, the experience is improving. “Newer digital mammography machines are being designed with `comfort paddles’ that distribute pressure more evenly, reducing the sensation of pinching,” says Dr Binay Shah, co-founder of the Binaytara Foundation, a non-profit organization in Bellevue, WA, that is dedicated to reducing cancer disparities, making evidence-based cancer care accessible, and improving patient outcomes worldwide. “Tomosynthesis [3D mammography] is another advanced technology that allows for clearer images with less compression, which can alleviate discomfort for some women.”

“Additionally, women can schedule mammograms after their menstrual period and inform the technician about their history of painful mammograms,” says Dr Fengting Yan, breast oncologist at True Family Women’s Cancer Center at Swedish Cancer Institute in Seattle. “Some other things they can do is consume less caffeine, avoid smoking, take a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, such as ibuprofen, 45–60 minutes before the screening and delay a mammogram screening if they are breastfeeding or have completed radiation therapy recently. Some mammography centers are also offering comfortable padding, such as the brand MammoPad.” (Clinical studies conducted in both the United States and Sweden examined the use of MammoPads in more than 1,300 patients, revealing that approximately 70% of participants experienced a notable reduction in discomfort when using these FDA-approved foam cushions during mammograms.)

Myth #3: Only women with a family history of breast cancer need mammograms

FACT: This misconception can be dangerous because most women diagnosed with breast cancer don’t have a family history of the disease. In fact, only about 10-15% of breast cancers occur in women with a family history of breast cancer.

The disease can develop without showing any obvious signs, and if you wait to undergo a mammogram screening only after you have symptoms of breast cancer, such as a lump or discharge, the cancer could be considerably more advanced by then. In fact, a study published in the Journal of the American College of Radiology found that mammography could detect breast cancers 1-3 years before they would typically become symptomatic.

Myth #4: Mammograms are not effective for women with dense breasts

Fact: Breast density refers to the amount of fibrous and glandular tissue compared to fatty tissue in the breasts. Mammograms can detect cancer in women with dense breasts, but they may not be as sensitive as they are with fatty breasts.

Supplemental screening methods, such as breast ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are often recommended in such cases to discover anomalies in dense breasts that might have been missed during a standard mammogram screening.

“Traditional 2D mammograms capture only a single, flat image of the breast, which can make it difficult to differentiate between dense tissue and tumors as both appear white on the scan,” says Dr Binay Shah. “In women with dense breasts, this overlap of tissue can obscure abnormalities or create what is known as false positives. With the newer 3D mammography technology, however, you can take multiple low-dose X-ray images from different angles around the breast and reconstruct them into a series of thin slices. This allows radiologists to examine the breast tissue layer by layer, reducing the interference of dense tissue and improving the visibility of small tumors that may be hidden in dense breast tissue.”

Myth #5: If you have a normal mammogram screening result, you won’t get breast cancer

Fact: While a normal mammogram is a very positive indicator, it does not guarantee immunity from breast cancer.

Mammogram screening is designed to detect breast cancer early, often before symptoms appear. However, it only captures the state of the breast tissue at the time of the scan. A normal mammogram simply means no signs of cancer were detected at that moment, but breast cancer can still develop afterwards, even within a short timeframe.

There is also the concern about false negatives. Mammogram screenings, while effective, are not perfect. There is a chance of false negatives, meaning the mammogram does not detect cancer that is actually present. The American Cancer Society estimates that mammograms miss about 13% of breast cancers, and this can happen for a number of reasons, such as small or overlapping tumors, breast implants, dense breast etc.

This is why it is crucial to maintain regular mammogram screenings and stay vigilant about overall breast health.

Myth #6: Once you’ve had a mastectomy, you don’t need mammogram screenings

Fact: A mastectomy significantly reduces the risk of breast cancer but does not eliminate it entirely. During the surgery, most of the breast tissue is removed, but a small amount of breast tissue can still remain (particularly in areas near the chest wall or under the skin), and there is a small chance that cancer can return in this residual tissue.

For women who have had a bilateral mastectomy (removal of both breasts) and breast reconstruction, breast imaging such as mammograms, breast ultrasound or breast MRI may still be recommended, particularly if there are palpable abnormalities or concerns of implant rupture.

While the risk is lower after bilateral mastectomy, some experts suggest that imaging should continue in cases where there is residual tissue or a possibility of complications related to implants or reconstructive surgery.

Myth #7: Mammograms are unnecessary if you had a recent clinical breast exam

Fact: A clinical breast exam (CBE) and a mammogram are two distinct tools in breast cancer screening, and they are meant to complement, not replace, each other.

A clinical breast exam is a physical examination performed by a healthcare professional, where they use their hands to feel for lumps or abnormalities in the breasts. While it can help detect larger or more obvious lumps, it is limited in its ability to find smaller tumors that are not palpable, especially in the early stages of cancer.

In contrast, mammogram screening is an imaging technique that uses low-dose X-rays to capture detailed images of the internal breast tissue. Mammograms can detect cancers that are too small to be felt, sometimes up to three years before symptoms develop. According to the American Cancer Society, mammograms can identify early-stage breast cancers with an accuracy of around 85% to 90%, which is far more precise than a clinical exam alone.

Myth #8: You can’t get a mammogram screening if you are pregnant

Fact: Mammograms involve low-dose radiation, which often raises concern among expectant mothers. However, the radiation used in mammogram screenings is minimal, and precautions such as shielding the abdomen with a lead apron are used to protect the fetus. The American Cancer Society notes that the risk to the baby is extremely small, and mammograms can be performed if there is a clinical need, such as the detection of a suspicious lump.

Myth #9: Mammograms are ineffective for younger women

Fact: While breast cancer is more common in older women, it still affects younger women. (In fact, around 5% of breast cancers occur in women under 40, according to the American Cancer Society.)

Mammogram screenings can be useful for younger women who are at high risk of breast cancer due to family history, genetic mutations, detection of a lump or some other suspicious change in their breast health. In these cases, screening by mammograms and breast MRI may start earlier than the typical age of 40 recommended for average-risk women.

Myth #10: Mammogram screens are not effective after menopause

Fact: Breast cancer risk increases with age, and the majority of breast cancer cases occur in women over the age of 50. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reveals that nearly 80% of breast cancer diagnoses happen in women aged 50 and older. Therefore, mammogram screenings are even more vital during and after menopause when the risk factor is higher.

An interesting fact to note here is that mammography tends to be more effective after menopause. Many women have dense breast tissue before the onset of menopause, which can make it harder for mammograms to detect cancer. Postmenopause, breast tissue generally becomes less dense and more fatty, which makes abnormal masses or tumors easier to detect.

Myth #11: Breast implants make mammograms impossible

Fact: Breast implants do not make mammogram screenings impossible. Radiologists use a technique called implant displacement (Eklund technique), where the implant is gently pushed aside so that the breast tissue can be spread over the mammogram plates and scanned clearly. This allows more of the breast tissue to be seen and reduces the interference caused by the implant.

There’s a common misconception that mammograms can rupture breast implants. While mammograms do involve some degree of compression, the risk of implant rupture during a mammogram screening is very low.

Implants today are more durable, and while rupture is rare, the benefits of early breast cancer detection far outweigh this small risk.

Myth #12: Having a mammogram is dangerous because it causes cancer to spread

Fact: The belief that a mammogram could “spread” cancer stems from a misunderstanding of how cancer behaves. The disease spreads through a process known as metastasis, in which cancer cells detach from the primary tumor and migrate through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to other parts of the body.

This spread happens due to the behavior of cancerous cells themselves, driven by genetic mutations, not because of external forces like compression applied during a mammogram. The compression is designed solely to improve image clarity, and there is no scientific evidence that it influences cancer’s ability to spread.

Conclusion

As we observe National Mammography Day, let us commit to sharing factual information, busting myths and encouraging conversations about breast health. By doing so, we can help remove the stigma and fear surrounding mammogram screenings and ultimately save lives through early intervention. The fight against breast cancer is ongoing, and each informed decision we make contributes to a stronger defense against this disease.

• Article reviewed by Fengting Yan, MD, FACP, breast oncologist at True Family Women’s Cancer Center at Swedish Cancer Institute in Seattle.

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?

Share with your friends and family and help raise awareness about breast cancer!

Binaytara Foundation Hosts Inaugural Global Health Speaker Series “Perspectives in Global Health – exploring challenges and solutions”

Dr. Darya Kizub – Improving Early Detection of Breast Cancer in Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa